In the next few sections, we are going to take a closer look at some of the tools we use in our research. These are the basic components that we use to understand the social, cultural, spatial, and environmental world. Once you have familiarized yourself with these important tools, you will be ready to put them all together and answer scientific questions about life in Nang Rong.

|

May I Ask You Some Questions?

Have you ever filled out a survey? Who hasn't? In the United States and other developed countries, surveys are used for everything from opinion research to evaluating the friendliness of restaurant wait staff. Many of us have filled out so many surveys that we are tired of them, yet requests to take surveys keep coming - in the mail, over the phone, when we shop, and in pop-up windows on our computer screens and nearly everywhere else you go online. In the digital age, information can even be collected on our interests and other characteristics without our even knowing it - through the use of "cookies," software that tracks website user behavior, and other new web technologies.

Given that surveys are so commonplace in the United States and elsewhere, it might seem odd to ask where surveys and survey questions come from. After all, if someone wants to know the answer to something, they can just write up the questions they want answered and give them to as many people as they can find. Voila! Instant information! But those of us who design, conduct, and examine scientific surveys take a very different stance toward this issue. Anyone can produce a survey, it is true, but to produce a survey that will provide sound, reliable, and consistent results is not just an art - it is a science.

In order to produce information, theories, and conclusions that meet the high standards of the scientific community, the Nang Rong Project team must be knowledgeable in the science of surveying. While the subject is vast, a few basic principles underlie much of survey research. Let's take a look at each of these in brief.

A Representative Group

Have you ever participated in a telephone or internet poll? Maybe you voted for your favorite singer on a television program or sent a text-message to register support for a cause. Often, these "opinion polls" claim to represent the American population, or the population of a state, city, etc. Do they really? Most scientists would say no.

First, surveys of this kind exclude anyone who cannot participate because they lack the technology. This is becoming an ever-bigger problem in an era when many households now have either a cellular telephone or a "land-line" - and not both. If these groups are similar, that is, if people with cellular telephones represent the overall population, then it might not be a problem. But what if people without a traditional phone land-line are younger, more savvy with technology, or make more money on average than other people? If any of these or other differences exist, the survey no longer represents the entire population.

A second problem with this type of survey is that the people who respond, or respondents, are often self-selected. Imagine you work for a restaurant chain and one of your jobs is to collect and read the survey cards left on tables. Who is likely to leave responses? Quite likely they are people who either had terrible service or exceptional service. Rather than representing the general population of restaurant-goers, these survey responses represent only people whose views were strong enough to motivate them to fill out a card. Such information might be okay for some uses, but provides no basis for scientific research, which is judged by both how accurately and consistently it reflects reality.

Encouraging Participation

So how do scientists get those people "in the middle," those who do not feel particularly strongly about the subject of the survey to respond? Generally, they use two practices. First, they select people randomly to participate in the study - perhaps by making a list of all families living in an area. Second, they often make repeated attempts to contact the persons selected until they either agree or decline to participate in the survey. Obviously, the more fed-up with surveys a group of people is, the more of them will likely decline to participate. Fortunately for us, villagers in Nang Rong do not get asked to participate in many surveys, and so they were very willing to help us learn more. In fact, a response rate of 70% (7 out of every 10 persons asked agreeing to participate) is considered very good in survey-weary places like the United States. In Nang Rong, we obtained nearly 100% participation for each round of interviews. This is due in part to the lack of survey overload and the high regard for University Professors in Thailand, but also to intentional practices on the part of the research team. An important aspect of ensuring repeated cooperation is leaving the respondents with a good impression. Sharing the results of the survey with them, providing a small incentive for participation, and taking the time to personally get to know each respondent are some of the many ways to ensure that a group of people does not grow weary of taking surveys.

Asking Good Questions

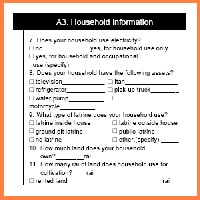

The questions that appear on a survey can be grouped for simplicity into two types: those that ask for closed- and open-ended responses. Closed-ended response questions provide the respondent with a number of answers to choose from. In contrast, with open-ended responses the researcher asks a question and then encourages the respondent to answer any way he or she wishes, carefully recording what is said. The researcher may ask follow-up questions that were not part of the original survey in order to clarify the respondent's meaning. The advantage of closed-ended questions is that the responses are easier to summarize. Sometimes it is as simple as counting up the number of "yes" and "no" responses. They can also be much easier to answer. Rather than forcing a respondent to recall the crops they planted last year, the researcher might ask a series of yes-or-no questions such as, "Did you grow rice? Did you grow sugar cane?" and so on. These questions are often easier to answer, and can jog a respondents' memory about a crop he or she planted but did not recall following the more general question. Open-ended questions, on the other hand, usually provide more information, and are especially useful when the researcher is not very familiar with a topic. In many cases, even experienced researchers will construct a set of responses that they believe is complete, only to find out later that they left out one or more important options. Suppose you were designing a survey about the places your fellow students went on vacation last summer. Could you create the list of all the places they visited that would be needed to ask a close-ended question? If so, would your set of responses be specific enough to tell you much about their trips? Writing good survey questions - those that invite meaningful responses but are summarized easily - is an often-overlooked, but crucial part of any survey.

Responding to Problems

No matter how well-thought-out a survey may be, when it comes time to put the plan into action, problems will arise. Some surveys are massive, not only do they seek thousands of respondents, but they may ask hundreds of questions that might take an hour or more to answer. This all adds up to a lot of questions and a whole lot of information! Inevitably, some people will misunderstand what a question is asking about. The risk of this is much greater if questions were written by a person living in one culture, translated into a second language, and answered by a respondent living in another culture. A vital step in constructing a survey in an unfamiliar language and place is testing the questions out with a small group of potential respondents. During this "trial run," the participants are presented with a potential question, and then asked to comment on the question, point out unclear sections, suggest improvements, and so on. This process may uncover additional responses for close-ended questions that need to be provided, as well as areas for open-ended responses to probe further.

Even with these additional steps, mishaps will occur, and a good researcher must be prepared to make decisions and adapt to conditions quickly. These mishaps can take many forms, ranging from poor translations, both minor and major, to entire sections of a questionnaire needing to be re-thought on the fly in response to confusion or failure.

One example from our own survey involves the difference between owning a parcel of land and using it to grow crops. Coming from a cultural background where most farmers today own the land they farm, or have a formal arrangement to use or rent the land from the landowner, we were not well-prepared for the complexity of land ownership and use in Nang Rong. During initial rounds of question-testing, we found that asking about who owned a given parcel of land was not a good way to obtain the information we wanted for several reasons. First, some households did not have a formal right to the land they were using, while others shared ownership of land jointly. Still others were reluctant to let others know they owned a given parcel. Pushing our respondents to divulge the true owner of a plot may have generated conflict between neighbors or siblings over who owned, or had inherited a parcel of land. This is an example of a time when a researcher must behave responsibly and not ask a question that could cause actual harm to a person who answered it. A second major problem in finding out about land ownership was the concept of the parcel itself. As you may recall from Section 3 on climate, rice is grown in paddies separated by bunds. A single farmer may use several paddies next to each other, or intermixed with those of another farmer, to grow different varieties of rice. Our simple notion of fields of a single crop did not fit with the complex agricultural landscape of Nang Rong.

Through continued discussions with the people living in Nang Rong, we came to a solution that helped with both problems. We asked each household about the land that it used. To clear up ambiguity about the extent of the land use, we used the actual Thai word plang, which had no good translation in English, but roughly meant a small piece of land used for farming a single crop. We were sure to ask households about all plangs that they used for any purpose, including those that they shared the use of with others. Through careful pre-testing and a willingness to change course in the face of a problem we were able to avoid the many pitfalls of asking about land ownership and get a fairly complete picture of all the lands a household actually used.

As you can see, one of the benefits of doing longitudinal research that goes back and asks the same people questions over time is that lessons learned from each round of interviewing respondents can be used to improve on the quality of the survey used in later rounds.

ABOVE: It is especially important in crafting questions for surveys in other countries that the questions be written or proofread by someone familiar with the culture. The vehicle pictured is an Itan, a multi-purpose vehicle whose engine can be removed from the truck and used to power farm equipment. A non-Thai, or even a Thai from a non-farming region, might not know to even ask about such a machine, even though they are both common and important in Northeast Thailand.

|

|