Faculty Fellow Whitney Robinson publishes COVID-19 response in Insight

Faculty Fellow Whitney Robinson published a response “Known Knowns, Known Unknowns, and Unknown Unknowns: the Complexities of COVID-19 Vaccine Prioritization” in Insight, a new publication started by UNC SILS Associate Professor Zeynep Tufekci.

An excerpt:

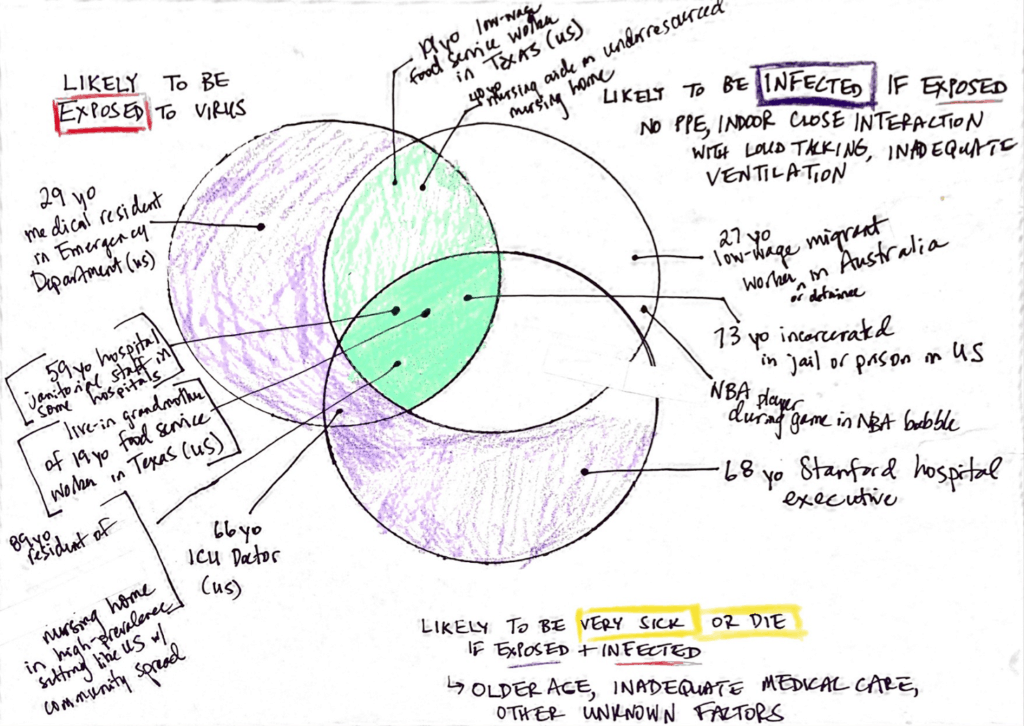

Using a black marker, my kids’ crayons and a large peanut butter jar, I drew three overlapping circles. The one of the left was for those at high risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. The one on the right was for settings characterized by high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection if exposed. And, finally, the bottom circle was for those with high infection fatality rates, the people most likely to die if exposed and infected with the novel coronavirus.

By putting a few examples in the diagram, I tried to make a few points:

- Exposure risk can vary as much as IFR. On a given day in December 2020, a 30-year-old Stanford resident working in the Emergency Department has a coronavirus exposure risk of basically 100%. In contrast, because of their financial resources and medical knowledge, the Stanford work-from-home senior faculty can have a risk approaching zero if they take all precautions available to them. Let’s conservatively say that, on any given day, the exposure risk for the Stanford resident is about 100 times higher than for the senior faculty member. I’m assuming the senior faculty has a 1.0% risk of exposure every day, which I think is a big overestimate. but the point is the scale: like the IFR, exposure risk can vary by orders of magnitude across the population. In this case, the 100-fold difference in exposure risk is the same as the IFR between a 70-year-old and a 30-year-old. There are circumstances where exposure differences are so large that they essentially cancel out the IFR: a heavily exposed 30-year-old can be as likely to die of COVID-19 as a 70-year-old with 1/100th the exposure risk.

- Infection risk matters. Exposure is not enough to cause infection. With proper mitigation (like the PPE, protocols, and ventilation available to doctors at Stanford), infection risk can be dramatically reduced. See the purple area in the Venn diagram.

- Most importantly, even among those who are high-risk because of older age, there is a subset that is even *higher* risk. I denote these folks in dark green in the Venn diagram. They are biologically susceptible (high IFR) because of their age, but they are also disproportionately likely to be exposed in high-infection circumstances. These folks are the highest of the high risk. Vaccinating these folks first would reduce mortality most dramatically.